In my last post, I talked about splitting up sentences of text and using Regex to turn a longer string into an array of objects representing fragments of a sentence. We also created a basic expression parser to convert a sentence containing two parts, a Day and a Time, into a single DayTime object. On top of this, we considered the following scenarios:

// Separate two part element context

"Pickup Mon 08:00 dropoff wed 17:00"

// Range elements with different separators

"Open Mon to Fri 08:00 - 18:00"

// Repeating tokens

"Tours 10:00 12:00 14:00 17:00 20:00"

// Repeating complex elements

"Events Tuesday 18:00 Wednesday 15:00 Friday 12:00"

Expression Trees

Selecting exactly two values into a single object is simple, but when things become combinations of conditional, repetitive or optional rules, the patterns cannot be easily configured in a single phase pattern match. We need a better understanding of the pattern structure in order to begin to solve it with code. For this, we are going to need to define our sentences as expression trees, with the root being the complete concept we are parsing.

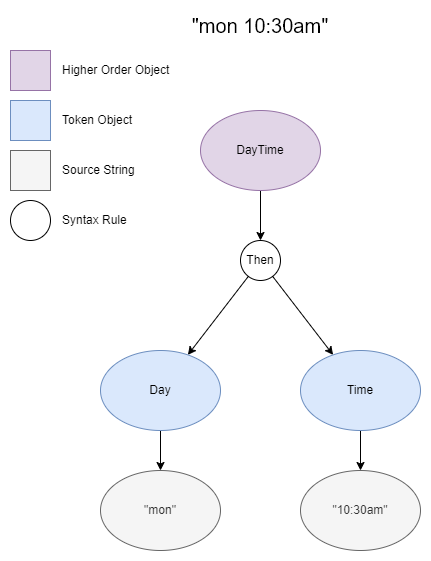

You read an expression tree from left leaf to right leaf, with each branch node being a syntax rule and each leaf element being a token extracted from the original sentence. We can start by describing our original parsing subject, DayTime:

This is simple enough, but our sentences are more complex concepts than this, a higher order object can be composed of other higher order concepts, and what is a root for some scenarios may be a child for others. Consider the expression trees for the scenarios above:

| Pickup / Dropoff | Range seperators | Repeating Tokens | Repeating Complex Children |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Basic Parser Rules

In order to begin to process the above scenarios, we’re going to need something to handle our expression rules, let’s stick with those needed just for handling DayTime for now:

- IsToken - A parser that matches a single token. (These would be the blue Token nodes in the tree)

- Then - A parser that matches two consecutive parsers together in a chain.

- Select - A parser that converts the result of one Parser into a different result type. (These would be the purple higher order nodes in the tree)

Parser Chaining

How do you start to combine these together? We are in a situation where we have a list of tokens we want to provide to a parser, but we also need to put a parser inside another parser and do some magic… We’re missing some key concepts. Let’s go back to our naive parser implementation:

public interface IParser<T>

{

ParseResult<T> Parse(Token[] tokens);

}

public class ParseResult<T>

{

public bool Success { get; init; }

public T Value { get; init; }

}

We can’t really chain this. Our input is always a Token[] array, and our output is always a result of processing the complete input. But what if an instance of a parser only consumed the tokens that were relevant to itself and its children, and returned the remaining tail? How would we do that?

We can create a Position object that encapsulates our Tokens and Ordinal:

public class Position

{

public Position(Token[] source, int ordinal)

{

Source = source;

Ordinal = ordinal;

}

public Token[] Source { get; }

public int Ordinal { get; }

public Token Current => !End ? Source[Ordinal] : throw new ApplicationException("At End");

public bool End => (Ordinal == Source.Length);

}

From here, if we change the input to Position and we add a Position to the response, then when we take the a successful Parse attempt that has moved the Ordinal forward, we can feed that relative Position into the next parser in the expression tree, and we’ve opened up the possibility of chaining and composition.

public interface IParser<T>

{

ParseResult<T> Parse(Position position);

}

public class ParseResult<T>

{

public bool Success { get; init; }

public T Value { get; init; }

public Position Position { get; }

}

Now let’s look at some implementations to get an idea of what they do individually.

Basic implementations

IsToken

We can start with the most basic check, see if the current position is a match for the Token, and if it is, return the next position and the result, otherwise return a failure at the current position. We’ll use this to check for Day and LocalTime.

public class IsToken<T> : IParser<T>

{

public IsToken() { }

public ParseResult<T> Parse(Position position)

{

return position.Current.Is<T>() ?

ParseResult<T>.Successful(position.Next(), position.Current.As<T>()) :

ParseResult<T>.Failure(position);

}

}

Then

The Then implementation contains a first parser, representing the syntax on the left, and a function to generate the second parser, which we run and use to evaluate the syntax on the right but only if the first parser is successful. In our scenario, we will be looking for an Is<DayOfWeek> on the left, followed by Is<LocalTime> on the right.

public class Then<T, U> : IParser<U>

{

IParser<T> _first;

Func<T, IParser<U>> _second;

public Then(IParser<T> first, Func<T, IParser<U>> second)

{

_first = first;

_second = second;

}

public ParseResult<U> Parse(Position position)

{

var result = _first.Parse(position);

position = result.Position;

if (!result.Success)

return ParseResult<U>.Failure(position);

var thenResult = _second(result.Value)

.Parse(position);

position = thenResult.Position;

return thenResult.Success ?

ParseResult<U>.Successful(position, thenResult.Value) :

ParseResult<U>.Failure(position);

}

}

Select

Select takes a core Parser as an argument and a converter function. When the core parser is successful, the result is fed into the converter function and the converted result is returned. Here, our converter method will pass in the previous two values and generate our DayTime.

public class Select<T, U> : IParser<U>

{

IParser<T> _core;

Func<T, U> _converter;

public Select(IParser<T> core, Func<T, U> converter)

{

_core = core;

_converter = converter;

}

public ParseResult<U> Parse(Position position)

{

var result = _core.Parse(position);

position = result.Position;

return result.Success ?

ParseResult<U>.Successful(position, _converter(result.Value)) :

ParseResult<U>.Failure(position);

}

}

Using this pattern, we can build a tree of parsers to represent our expression and run this over our Token array.

Putting it together

Let’s take our original naive parser for DayTime, and replace it with our new parser setup.

public static IParser<DayTime> DayTimeParser =

new Then<DayOfWeek, DayTime>(

new IsToken<DayOfWeek>(),

dow => new Select<LocalTime, DayTime>(

new IsToken<LocalTime>(),

lt => new DayTime { Day = dow, LocalTime = lt }));

Ok - it works, it’s got the Is<DayOfWeek>(), Then(), Is<LocalTime>(), Select<DayTime>() pattern, but this isn’t particularly fun to work with. There are lots of new keywords and the code reads like Polish notation.

Making it fluent

To make things easier, we can create a bunch of static helper methods to configure our root parsers, and a set of extension methods to combine our parsers together:

public static class Parsers

{

public static IParser<T> IsToken<T>() =>

new IsToken<T>();

public static IParser<List<T>> ListOf<T>(IParser<T> parser) =>

new ListOf<T>(parser);

public static IParser<T> Or<T>(params IParser<T>[] options) =>

new Or<T>(options);

}

public static class ParserExtensions

{

public static IParser<U> Then<T, U>(this IParser<T> core, Func<T, IParser<U>> then) =>

new Then<T, U>(core, then);

public static IParser<U> Select<T, U>(this IParser<T> core, Func<T, U> select) =>

new Select<T, U>(core, select);

public static IParser<T> End<T>(this IParser<T> core) =>

new End<T>(core);

}

Then we can re-write our original implementation using a fluent approach to compose our parser tree, with the result being much cleaner:

public static IParser<DayTime> DayTimeFluentParser =

Parsers.IsToken<DayOfWeek>().Then(dow =>

Parsers.IsToken<LocalTime>().Select(lt =>

new DayTime { Day = dow, LocalTime = lt }));

But this is only a parser for our basic scenario, right? We’ve added a whole bunch of code, complexity and fluff, with no new functionality, and we’re still left with only this?

Composition

Well… not quite. Now we can create parsers from other parsers; that’s what we did when we created our DayTimeParser from Is<DayOfWeek> and Is<LocalTime> checks, so let’s take our pickup / dropoff scenario above, where our DayTimeParser can point to either of our fluent/non-fluent implementations:

// This parser returns a DayTime where it is preceded by a PickupFlag

public static IParser<DayTime> PickupDayTime => Parsers

.IsToken<PickupFlag>()

.Then(_ => DayTimeParser);

// This parser returns a DayTime where it is preceded by a Dropoff flag

public static IParser<DayTime> DropOffDayTime => Parsers

.IsToken<DropoffFlag>()

.Then(_ => DayTimeParser);

// This parser returns a PickupDropOff object that is derived from a

// sequential Pickup/Dropoff match. Note that each of the Pickup/Dropoff

// parsers return a DayTime.

public static IParser<PickupDropoff> PickupDropOff =>

PickupDayTime.Then(pu =>

DropOffDayTime.Select(dr =>

new PickupDropoff { Pickup = pu, DropOff = dr }))

.End();

And that’s it, we’ve got our text with our pickup DayTime and our dropoff DayTime mashed together into a single object, using composition and some tidy fluent snippets.

Completing the set

We’re still pretty limited in terms of what we can do with our original Is/Then/Select parsers, we can’t cater to some of the more complex scenarios. We’re not done yet.

Or

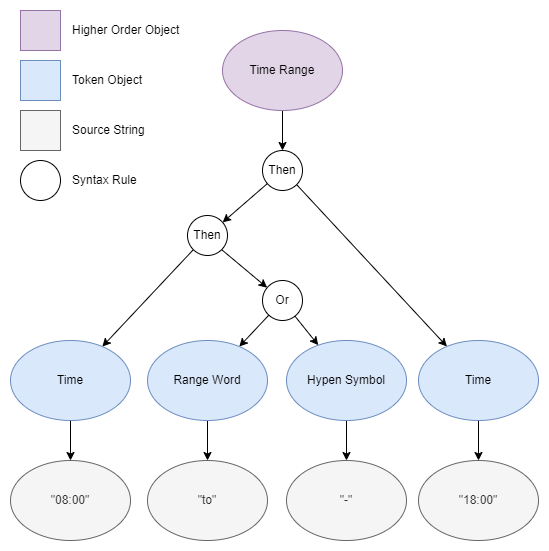

A parser that matches one of multiple child parsers of the same result type. Let’s say we want to treat two different Tokens the same way; we need something conditional in our expression to indicate that one expression must be a match. Let’s take an expression where we want to use “to” or “-“ to indicate that we are matching a term describing a range between two values.

public static IParser<RangeMarker> RangeMarker =

Parsers.Or(

Parsers.IsToken<HypenSymbol>().Select(r => new RangeMarker()),

Parsers.IsToken<JoiningWord>().Select(r => new RangeMarker())

);

We can then use this as part of a combination to satisfy either condition:

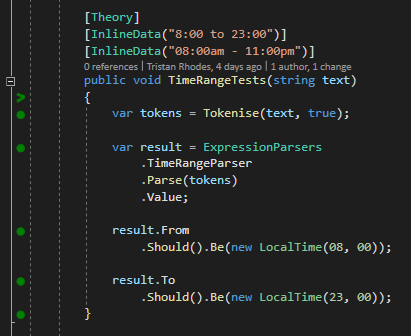

public static IParser<Range<LocalTime>> TimeRangeParser =

Parsers.IsToken<LocalTime>().Then(from =>

RangeMarker.Then(_ =>

Parsers.IsToken<LocalTime>()

.Select(to => new Range<LocalTime> { From = from, To = to })));

And we can match 12 or 24 hour clocks, separated by a range marker of “to” or “-“.

ListOf

A parser that matches a number of items against a single child parser and returns a list of the child parser values:

ParseResult<List<DayTime>> result = Parsers

.ListOf(DayTimeParser)

.Parse(tokens);

End

A parser that determines if the result is the end of the Token array. This prevents a match from being successful when there are unconsumed tokens from the complete parsing expression.

public static IParser<DayTime> ExplicitDayTimeParser =

DayTimeParser.End();

All of these lovely Parser implementations are available here, with the configurations for the original sentence structures here. There might even be some tests in there somewhere.

Turtles

And after that… it all gets a bit, Turtles… all the way down…

So if you want to take this thought experiment a bit further, try thinking about (or implementing) lists of lists of complex objects…. or lists of lists of lists… or just n+1. Once you solve the problem at one level, you can solve it at any level.

Code

More code turtles are available here where I put together a bunch of different ways to do parsing. We’re currently still in the slavishly Object Orientated part, so check out the OO folder.

Next Up

So far, we’ve been good little object orientated boys and girls, we’ve got our Interface, we have our little implementation classes, we’ve got good SOLID principles, but it’s still pretty heavy… this interface is only a single method.

public interface IParser<T>

{

ParseResult<T> Parse(Position position);

}

Does it need to be an interface? What else could it be?

public delegate ParseResult<T> Parser<T>(Position position);

Credits

Header Image by Glen Carrie on Unsplash