Brief

This post is part of a series that covers the concept of resilience in a distributed environment, and how to improve a systems handling of transient errors.

Posts

- Part 1 - System failure and Resilience

- Part 2 - Implementing Resilience

- Part 3 - Benefits of Resilience

Implementing Resilience

In my last post I talked about what resilience is, and what kind of behavior a system that isn’t resilient exhibits.

So how do we get around these issues, and what can we do in our code to ensure that we don’t fail needlessly? How do we prevent our systems generating thousands of error messages for things that are actually relatively predictable and shouldn’t be a cause for immediate alarm?

How do we implement resilience?

Identifying fatal vs not fatal errors

The first step is to identify fatal and non-fatal errors. If your service throws an argument null or null reference exception every time it is called, you cannot build resilience around that. If your service crashes and stops when a service call is made, there is not a lot you can do. These are fatal errors that cannot be recovered from. On the other hand, a well designed system can return a 503 error when it encounters a problem that should be temporary, such as a mutex or transaction lock, or resource timeout. These types of errors can occur from time to time and we can be confident that they do not necessarily need to be fatal. So what do we do with these errors?

Retry Mechanism

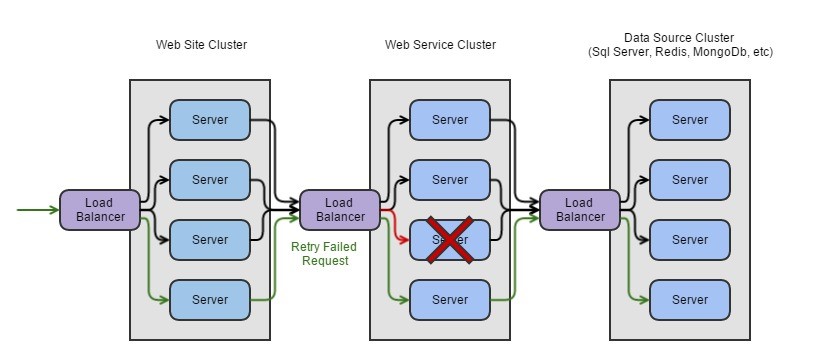

As mentioned above, if the server returns a 500 internal error, then that is fatal and we have no choice but to propagate it up the call chain, or handle it gracefully at the current level and return a meaningful message to the consumer. But a non-fatal error is something that we can retry after a brief period of time, confident that we could receive a different result:

To improve the resilience beyond a single retry, we can attempt multiple retries, and apply gradual throttling to slow the retry frequency down, trying first after one second, then two, then three, until we succeed, or our retry limit is reached.

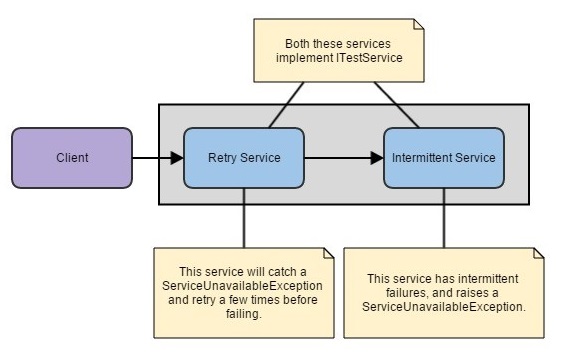

Retrying in an AOP Pipe

The best way to implement this mechanism is via an AOP pipe. We create a chain of implementers for a given interface, in this case ITestService, then run all of our operations through that. We build up our pipe with resilience features and make the service call itself significantly more robust.

Circuit Breaker Mechanism

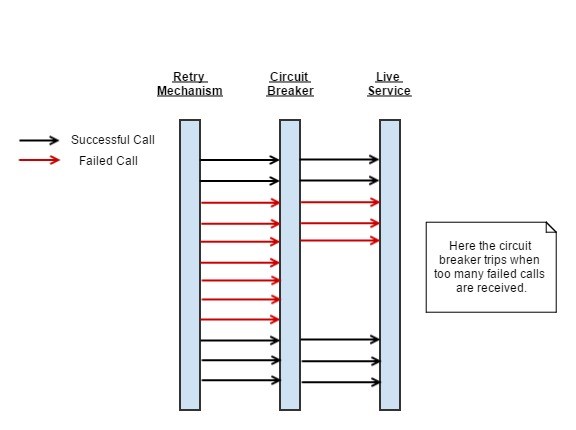

In conjunction with retrying, we can use a circuit breaker mechanism. If we have a system under high load, and we find ourselves failing hundreds or thousands of consecutive requests, what does that mean? Something is down, and what happens? Some error logs? Emails? Performance counters ticking?

I was once responsible for a scenario where a service was churning the first item in a message queue. The problem wasn’t discovered until pre-production, where it generated around 15000 emails in ten minutes to some senior people, flooded our exchange server and caused some ‘upset’. This much data is not useful. It can cause panic when none is necessary, and can hide other issues that may crop up in the meantime.

If we have a server that handles many thousands of incoming requests per second, and relies on an external resource which is down, then the service can benefit from a circuit breaker mechanism underneath the retry mechanism to alleviate load on the target service while it recovers.

This approach can be used to prevent running operations that have a high failure rate, particularly behind a retry mechanism. If we are being flooded by thousands of requests and our system begins generating a lot of errors, then shutting off that part of the system temporarily and failing without making the call is a much better way of dealing with these errors than continuing to hammer the target system.

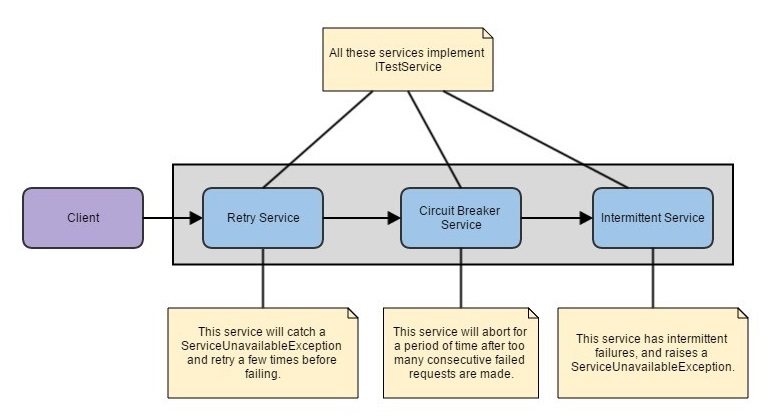

Circuit Breaking in an AOP Pipe

Just like the solution to apply a retrying mechanism as part of the AOP pipeline, we can inject a circuit breaker mechanism the same way. This would go in after the retry mechanism, as the retry mechanism can generate a higher volume of requests than it receives.

Sample Code

Let’s start with a basic interface:

public interface ITestService

{

void Execute();

}This interface is then implemented by a number of classes used in the pipeline:

- IntermittentService – Service that toggles on / off every 4 seconds. When off, raises ServiceUnavailableExceptions on Execute() calls.

- RetryService – Service that will catch any ServiceUnavailableExceptions and retry them 3 times, once every 1.5 seconds.

- CircuitBreakerService – Service that will catch any ServiceUnavailableExceptions and switch to an Open state for half a second when 2 consecutive requests fail.

The bootstrap process for building up these AOP pipelines is going to look quite familiar.

_rawService = new IntermittentService();

_retryService = new RetryService(

new IntermittentService());

_retryCbService = new RetryService(

new CircuitBreakerService(

new IntermittentService()));With the constructors all following the pattern of Constructor(ITestService next).

Functional Approach

Alternatively, for anyone who has watched the 8 lines of code video from Greg Young, we can use a functional programming approach to bootstrapping which strips out a lot of the boilerplate constructor logic and leaves us with just the function meat:

public class FunctionalService

{

public Action Bootstrap()

{

return new Action(

() => RetryService(

() => CircuitBreakerService(

() => IntermittentService())));

}

private void IntermittentService()

{

// TODO: Implement intermittent behavior.

}

private void RetryService(Action next)

{

// TODO: Implement retry policy

next();

}

private void CircuitBreakerService(Action next)

{

// TODO: Implement circuit breaker policy

next();

}

}

Conclusion

In part one, we covered what resilience was and how it manifests in large systems. In this part, we covered how you can implement some basic resilience techniques using retry mechanisms and circuit breakers, and apply them in code using Aspect Orientated Programming. Next we are going to look at the benefits of this approach to the system we are implementing it in.